The interest in natural hydrogen, often referred to as white or gold hydrogen, is rapidly growing worldwide as a potential revolutionary player in the quest for cost-effective, low-carbon energy sources.

According to Rystad Energy’s research, the number of businesses seeking natural hydrogen resources has increased significantly, from 10 in 2020 to 40 by the end of last year.

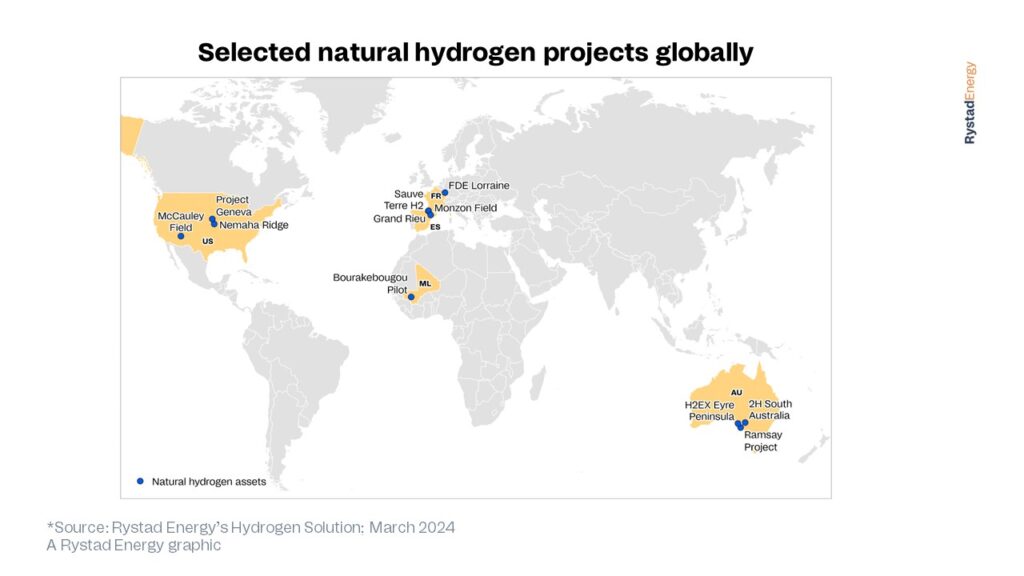

Exploration attempts are currently underway in various countries, including Australia, the United States, Spain, France, Albania, Colombia, South Korea, and Canada.

One of the key advantages of white hydrogen is its cost competitiveness compared to other forms of hydrogen.

Grey hydrogen, produced from fossil fuels, costs less than $2 per kilogram on average, while green hydrogen, produced using renewable electricity, is currently over three times more expensive.

Even as the cost of renewable hydrogen is expected to decrease with falling electrolyser prices, white hydrogen is projected to remain cheaper.

For instance, Canada-based producer Hydroma extracts white hydrogen at an estimated cost of $0.5 per kg.

Meanwhile, projects in Spain and Australia aim for a cost of approximately $1 per kg, showcasing white hydrogen’s price advantage.

Aside from its cost benefits, white hydrogen can also boast a low carbon intensity.

With a hydrogen content of 85 per cent and minimal methane contamination, the carbon intensity is around 0.4 kg carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) per kg hydrogen gas (H2).

This intensity increases to 1.5 kg CO2e per kg H2 with 75 per cent hydrogen and 22 per cent methane.

Rystad Energy Head of Hydrogen Research Minh Khoi Le notes: “Although still in its early stages with uncertainties, white hydrogen has the potential to transform the clean hydrogen sector as an affordable, clean natural resource, thereby reshaping hydrogen’s role from an energy carrier to part of the primary energy supply.

“However, the actual size of the reserves is still unknown, and challenges remain in the transportation and distribution of hydrogen.”

In the US, companies can receive production tax credits (PTC) under the Inflation Reduction Act if the lifecycle carbon intensity is below 4 kg CO2e per kg H2.

The highest PTC tier grants $3 per kg for hydrogen production meeting a carbon intensity threshold of 0.45 kg CO2e per kg H2.

This makes low-carbon white hydrogen production in the US particularly attractive for producers.

Despite an accidental discovery in Mali around 37 years ago, the accumulation of underground hydrogen was previously thought to be improbable due to its ability to permeate rock layers.

However, recent advancements, such as hydrogen-sensing gas probes, can now detect dissolved hydrogen in rock formations at depths of up to 1,500 metres, with ongoing research for probes to reach up to 3,000 metres underground.

White hydrogen is primarily produced through natural processes like serpentinisation, where water reacts with iron-rich minerals at elevated temperatures.

Enhanced serpentinisation, using catalysts such as magnetite, could accelerate natural hydrogen-producing reactions.

Another source of natural hydrogen is the radiolysis of water, where radioactive elements in the Earth’s crust split water molecules due to ionising radiation.

The South Australian government included hydrogen on its list of regulated substances in 2021, leading to an influx of companies applying for exploration permits.

Gold Hydrogen, for instance, secured a five-year licence to develop its Ramsay project and discovered high hydrogen concentrations of up to 86 per cent during drilling in late 2023.

The company plans further drilling in 2024 and a pilot feasibility study.

Governments in countries like France and the US have pledged financial support to expedite the exploration and extraction of naturally occurring hydrogen projects.

Currently, only one operational white hydrogen project exists in Bourakebougou, Mali, producing approximately five tonnes of hydrogen annually.

This small-scale project, operational for a decade, provides power to a village.

Other projects worldwide are still in the early exploration stages, with the first European natural hydrogen production expected to begin in 2029.